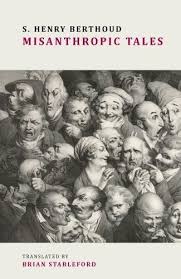

Snuggly Books, 2018

originally published as Contes Misanthropiques, 1831

translated by Brian Stableford

282 pp

paperback

There are times when I get to the end of a book and I think "really, that book shouldn't have ended the way it did ...in the real world that wouldn't have actually happened." In this collection of 35 tales, Berthoud takes that line of reasoning a step further and offers us stories with endings that could have actually happened, in a real-world sort of way. As translator Brian Stableford tells us in his introduction to this volume, these tales "defy and deny" normal fictional conventions. As he notes,

"what the great majority of readers want, most of the time, is to hear uplifting stories of heroic struggles of adversity, in which love conquers all,"but these contes cruels, as Stableford explains,

"are produced by writers who are painfully aware that this is not the way things work in the real world..."While this is my first experience with these stories written by Berthoud, I'm no a stranger to contes cruels, and I enjoy them precisely for that reason. They are cynical and hypocritical, and for readers who can pick up on that cynicism and hypocrisy there are great rewards. For me it's all in the twist -- and this book is no exception. There are some stories in here that produced a slight case of the giggles; some make their points in a much darker tone, but they're all wonderful examples of early contes cruels, a type of French fiction that I absolutely love.

While I can't possibly give each and every story the time here it deserves, there are two that get right to the point of this book. The first one is "Agib, or Wishes," in which a Caliph who has just recently ascended the throne needs someone to, as he puts it, "relieve my ennui." Seductive dancers don't seem to do it, so he looks to someone to relate "such beautiful tales" as his old nurse did. His wish is granted, the story of Agib is told, and yet, at the end of it all the Caliph complains:

"a moral is a moral, and it's too bad to want to make one by causing people chagrin, when one only ought to seek to amuse them."The storyteller, one supposes, isn't quite up to par with the old nurse, who told the most "beautiful tales."

The second story that hits the nail on the head is "The Hunchback: A Spanish Story" in which a stranded traveler learns from his gracious host that he should

"Examine attentively the most hideous vices, and the most heroic virtues; they take their source from egotism."Of course, our traveler disagrees, but discovers in the long run that the hunchback was not far from wrong. I was a bit taken aback at how this idea pops up right here, toward the very end of this book, and that made me mentally run through the all the stories up to that point before deciding that yes, he was absolutely correct in his assertion.

|

| the author, from Wikipedia |

While all of the stories in this book are quite good, I do have a few particular favorites aside from the two I've just mentioned. My very favorite piece is "Prestige," in which a young man, "young and in love," runs into an old friend. Things would have been better for him if he hadn't; even more so for the young woman he loves. This one has a sort of Bluebeard-ish vibe with a shocker of an ending I didn't even see coming. Next comes "Alice," about a woman whom life has treated poorly since childhood. After years of torment and melancholy, she finally meets the man of her dreams who offers her a way out of her suffering. The catch is that he has to return home to tell his mother; when that doesn't work, he offers another alternative. "The Painter Ghigi" follows, revealing the secrets of a tormented soul who cannot possibly escape the "secret pain" eating at him. Despite the strange and dark events of "The Enjoyments of Death," this one nearly made me laugh out loud when all was revealed. Then there's "Nocturnal Terror," in which a group of companions out for a nice day find themselves benighted at an old ruined manor house on their return to Edinburgh. Around a peat fire one of their number delights in the "vague and insurmountable terror" of his companions as he regales them with ghost stories, but there is nothing delightful at all in what happens when the stories are over and everyone goes off to bed. Finally, rounding out my top tier is "The Nose," which I can't even begin to rehash or it will ruin potential readers' surprise.

I have to pass on kudos to Snuggly Books for bringing this book into print; I enjoyed it so much that even before I'd finished I bought a copy of Berthoud's Martyrs of Science published by Black Coat Press, also translated by Brian Stableford. If you notice that many of these tales start to seem the same, well, there is something to that, but to me that didn't matter so much as the pleasure I got from reading them. Highly recommended -- it would be a great starting point as an intro to contes cruels; after Berthoud, as time goes on, the writers of these contes move into darker territory, but that same sense of understanding how things work in the real world never changes. They are among my favorite sorts of stories, along with darker contes fantastiques -- and I am always on the lookout for more.

No comments:

Post a Comment

feel free to say what you'd like, but please be nice about it.